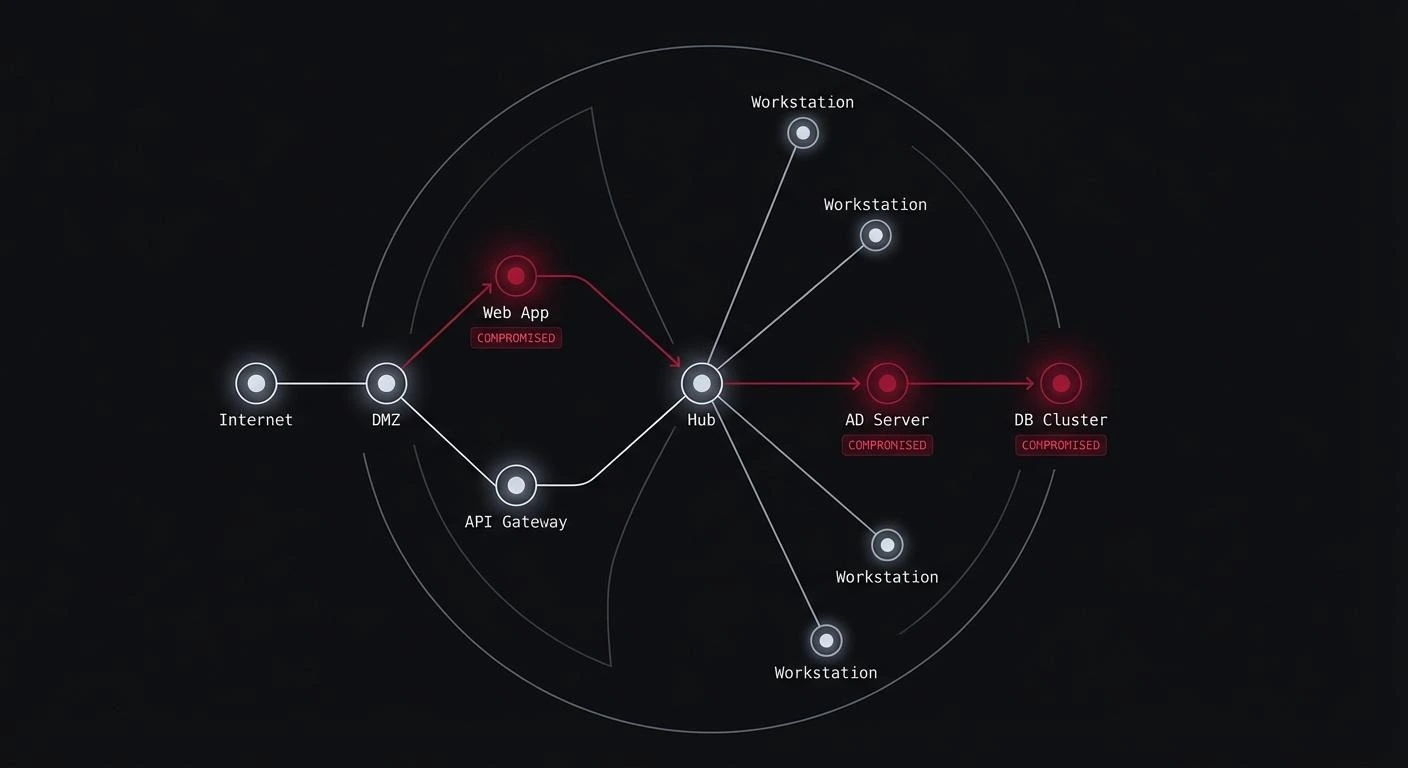

While reviewing the decompiled code of various macOS services, I discovered what appeared to be a textbook format string vulnerability in Apple’s TCC daemon (tccd)—the service that handles all those privacy permission prompts you see on macOS. The bug looked pretty straightforward at first glance: an asprintf call missing its format arguments. A classic mistake that typically leads to an easy exploit, right?

As we will find out, well, not really. Turns out not all format string vulnerabilities are exploitable if they’re handled properly at a lower level. This article documents a real-world format string vulnerability case study that reveals important lessons about decompiled code accuracy and vulnerability assessment. Enjoy!

The Initial Discovery: Format String Vulnerability in tccd

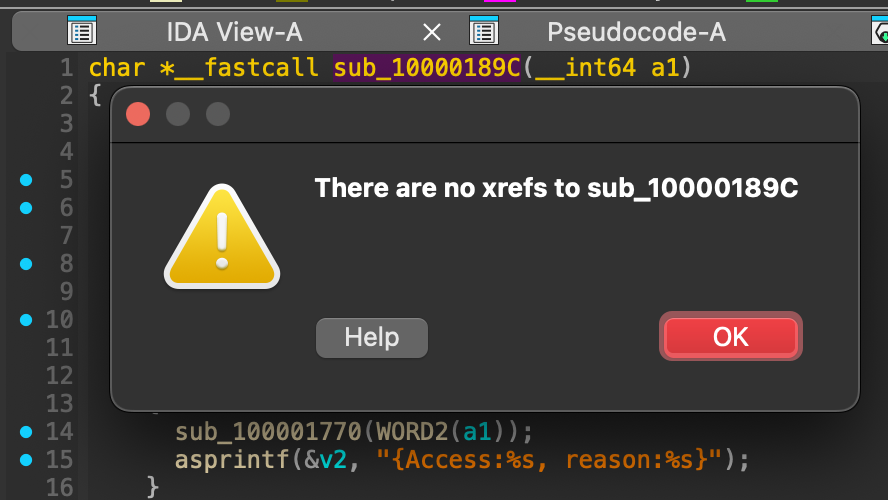

While reverse engineering the TCC daemon (tccd), I found the function sub_10000189C that had a problematic line that appeared to be a classic format string vulnerability:

Anyone who’s done some security auditing can spot the issue immediately – this format string expects two %s arguments, but none are provided. The proper way of using asprintf should be:

asprintf(&v2, "{Access:%s, reason:%s}", access_string, reason_string);When asprintf tries to read those missing arguments from the stack, it’s going to grab whatever garbage is sitting there, potentially leading to memory disclosure or code execution. This is a textbook format string vulnerability.

Reproducing the Format String Vulnerability: Proof of Concept

I rewrote the part of this code in a proof-of-concept to demonstrate the format string vulnerability:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdint.h>

char *vulnerable_function(uint64_t a1) {

char *v2 = NULL;

if ((a1 & 0x100000000000000ULL) != 0) {

if ((a1 & 0x200000000000000ULL) != 0) {

asprintf(&v2, "Auth:{Access:Unknown}");

} else {

asprintf(&v2, "{Access:%s, reason:%s}"); // Vulnerability here

}

} else {

asprintf(&v2, "Auth:{Invalid}");

}

return v2;

}

int main() {

uint64_t input = 0x100000000000001ULL;

char *result = vulnerable_function(input);

printf("Returned: %s\n", result);

free(result);

return 0;

}Detecting Format String Vulnerabilities Using AddressSanitizer

We can run this with AddressSanitizer to see a crash with invalid memory reads. Even without the sanitizer during compilation, the compiler will throw a warning about this format string vulnerability:

❯ clang -fsanitize=address -o poc poc.c

poc.c:13:37: warning: more '%' conversions than data arguments [-Wformat-insufficient-args]

13 | asprintf(&v2, "{Access:%s, reason:%s}");

| ~^

1 warning generated.At runtime, we can observe ASAN invalid read:

❯ ./poc

poc(15748,0x1f9fd5f00) malloc: nano zone abandoned due to inability to reserve vm space.

AddressSanitizer:DEADLYSIGNAL

=================================================================

==15748==ERROR: AddressSanitizer: SEGV on unknown address 0x000041b58ab3 (pc 0x0001052dc238 bp 0x00016b33e0e0 sp 0x00016b33d820 T0)

==15748==The signal is caused by a READ memory access.

#0 0x0001052dc238 in __sanitizer::internal_strlen(char const*)+0x4 (libclang_rt.asan_osx_dynamic.dylib:arm64e+0x54238)

#1 0x0001052a41a4 in vasprintf+0xa8 (libclang_rt.asan_osx_dynamic.dylib:arm64e+0x1c1a4)

#2 0x0001052a47b4 in asprintf+0x38 (libclang_rt.asan_osx_dynamic.dylib:arm64e+0x1c7b4)

#3 0x000104ac0958 in vulnerable_function poc.c:13

#4 0x000104ac0a3c in main poc.c:27

#5 0x00018bb26b94 in start+0x17b8 (dyld:arm64e+0xfffffffffff3ab94)

==15748==Register values:

x[0] = 0x0000000041b58ab3 x[1] = 0x0000000000000000 x[2] = 0x0000000000000000 x[3] = 0x000000016b33f2c8

x[4] = 0x0000000000000001 x[5] = 0x0000000000000020 x[6] = 0x0000000000000041 x[7] = 0x0000000000000000

x[8] = 0x0000000000000000 x[9] = 0x000000016b33e9a8 x[10] = 0x0000000000000073 x[11] = 0x0000007020978176

x[12] = 0x0000000000000002 x[13] = 0x0000000000000007 x[14] = 0xf9070000f9f9f9f9 x[15] = 0x0000000000000000

x[16] = 0x00000001052a477c x[17] = 0x00000001fb028228 x[18] = 0x0000000000000000 x[19] = 0x000000016b33e910

x[20] = 0x0000000104ac0baa x[21] = 0x0000000105319b7e x[22] = 0x0000000105319a73 x[23] = 0x0000000105319a92

x[24] = 0xaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa x[25] = 0x000000016b33d880 x[26] = 0x0000000041b58ab3 x[27] = 0x00000000ffffffff

x[28] = 0x0000000000000068 fp = 0x000000016b33e0e0 lr = 0x00000001052a3768 sp = 0x000000016b33d820

AddressSanitizer can not provide additional info.

SUMMARY: AddressSanitizer: SEGV poc.c:13 in vulnerable_function

==15748==ABORTING

[1] 15748 abort ./pocSo there is clearly a bug exhibiting classic format string vulnerability behavior, but is it actually exploitable in the real TCC daemon?

Investigating Format String Vulnerability Exploitability in Real Systems

Is This Dead Code?

The next step was to determine how to trigger this format string vulnerability in the actual tccd binary. IDA could not find any cross-reference to this function, meaning it hasn’t found any calls, jumps, or data references to that function in its analysis:

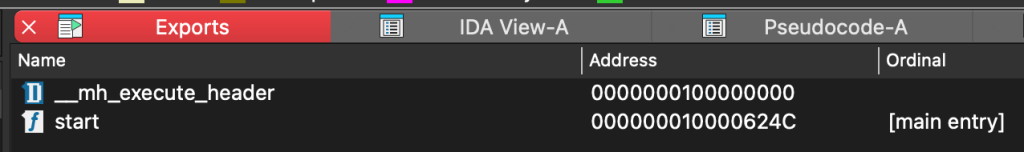

It doesn’t necessarily mean the code is unreachable. Sometimes, decompilers cannot handle things correctly, such as:

- Indirect calling – Functions can be stored in a jump table, virtual table, or function pointer array that IDA didn’t analyze properly.

- Dynamic linking – If the binary exports functions, it might be called by external code.

- Callback registration – Could be registered as a callback function somewhere else.

If this were a library, the function could be shared and found in the export table:

In other cases, to find references, we can:

- Search for the function address

10000189Cas a hex constant in the binary - Look for arrays of function pointers near this address range

- Search for any initialization code that might register this as a handler

Yet, after analysis, it seemed this function was never actually called; it was just dead code sitting in the binary, never executed. Maybe it is just Apple internal stuff left alone here.

Playing God

At this point, I could have just closed the case. Dead code isn’t exploitable. But I was curious. What if, in some future version of macOS, this function became reachable? Could it then be exploited? To answer this, I decided to play God with the debugger. I attached lldb to a running tccd process and manually hijacked the execution flow. I forced the program to jump directly into sub_10000189C:

# Attach to the second tccd process (user space tccd)

lldb -p `pgrep tccd | awk 'NR==2'`

# Set a breakpoint on the vulnerable asprintf call (inside sub_10000189C)

br set -s tccd -n ___lldb_unnamed_symbol458 -R 112

# Manipulate the registers to force the execution path

register write x0 0x100000000000000

register write pc 0x10247189c # this is sub_10000189C

# Continue execution

cThis is where the real surprise came. Even with the seemingly vulnerable asprintf call, the process didn’t crash. It behaved perfectly fine. How could this be?

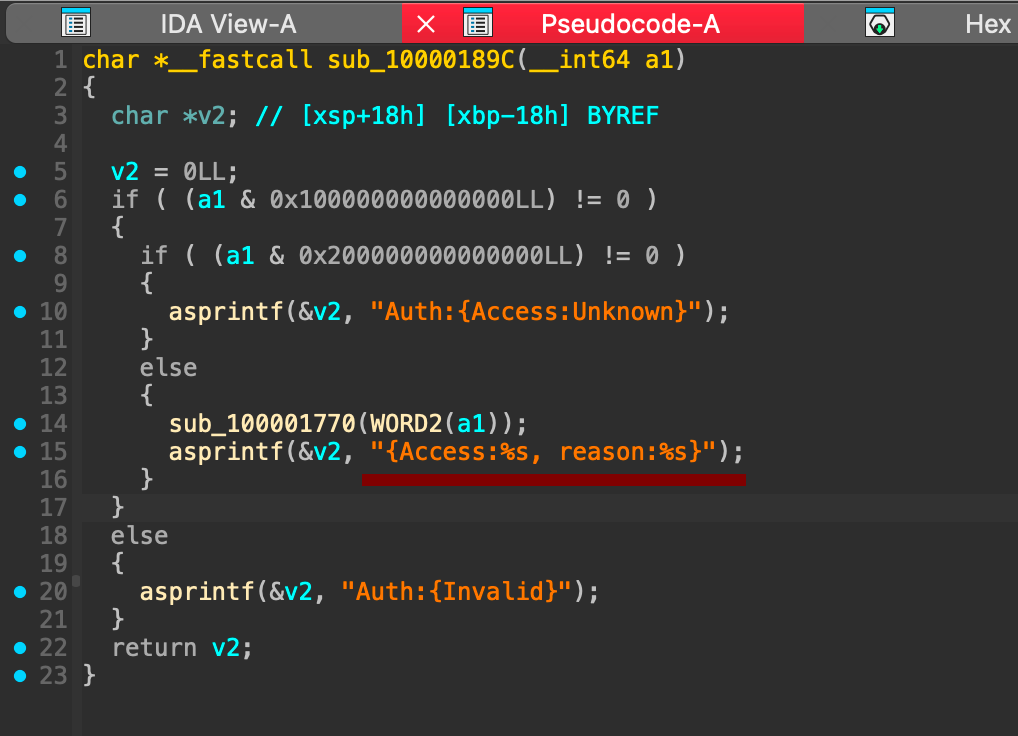

Why This Format String Vulnerability Isn’t Exploitable: Technical Analysis

Assembly to the rescue

Just before the “vulnerable” asprintf call, there was a call to another function, sub_100001770:

bl 0x102471770 ; Call sub_100001770, reason string is returned in x0

stp x19, x0, [sp] ; Store access string (x19) and reason string (x0) onto the stack

adrp x1, 108

add x1, x1, #0x862 ; Load the format string "{Access:%s, reason:%s}" into x1

b 0x102471918 ; Jump to the asprintf call

...

bl _asprintf ; Call asprintfThis sub_100001770 function’s job was to take an integer and return a corresponding reason string. The stp x19, x0, [sp] instruction takes the access string (e.g., “Denied”) from the register x19 and the reason string returned by sub_100001770 (in register x0) and stores them both at the top of the stack. On a breakpoint hit, I could see these two values at the top of the stack:

0x16d98e190│+0000: 0x00000001024dd83e → ("Denied"?) ← $sp

0x16d98e198│+0008: 0x00000001024dd75c → ("None"?)The Missing Format String Function Arguments

These are the missing format arguments. They were actually being “provided” by the sub_100001770 function that had placed valid string pointers on the stack exactly where asprintf expected to find them. So while the code is technically incorrect at a high level, because asprintf is missing explicit arguments, it works on a low level, because of the calling convention and stack layout. The last point of failure could be the sub_100001770, since it is responsible for what is placed on the stack. Here is the full code:

const char *__fastcall sub_100001770(__int64 a1)

{

if ( a1 > 5 )

{

if ( a1 <= 1001 )

{

switch ( a1 )

{

case 6LL:

return "Set";

case 1000LL:

return "Error";

case 1001LL:

return "Service Override";

}

}

else

{

if ( a1 <= 1003 )

{

if ( a1 == 1002 )

return "Missing Usage String";

else

return "Prompt Timeout";

}

if ( a1 == 1004 )

return "Preflight Unknown";

if ( a1 == 2000 )

return "Entitled";

}

return "<Unknown Reason>";

}

if ( a1 <= 2 )

{

switch ( a1 )

{

case 0LL:

return "None";

case 1LL:

return "Recorded";

case 2LL:

return "Service Default";

}

return "<Unknown Reason>";

}

if ( a1 == 3 )

return "Service Policy";

if ( a1 == 4 )

return "Compatibility Policy";

return "Override Policy";

}But it is secure. Even if an attacker reaches it, the logic handles all edge cases and just return reason_string, which in fact place it as a second value on the stack.

Final words

It’s important to note that the source code of the tccd is closed. The decompiled version is never a perfect representation. Compiler optimizations could also alter the behavior during compilation. The original code might have asprintf handling its arguments correctly. I focused only on the macOS 15.5 version of tccd. Older versions may use this code, or the code could be activated and used improperly in the future, potentially making the format string a real threat.

I hope this post illustrates how something that seems like a clear vulnerability at first glance may not actually be one. Until next time!