Introduction - Discovering PostgreSQL Injection in Enterprise Software

When you’re testing software like NetIQ Advanced Authentication – now known as OpenText Advanced Authenticator – a product trusted by enterprises, governments, and critical infrastructure, you can’t help but assume it’s already been thoroughly tested. Surely, if there were serious vulnerabilities like PostgreSQL injection, someone would’ve found them by now… right?

That assumption is where real testing begins.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of looking for only the obvious issues. What’s harder – and far more rewarding – is taking the time to understand how the application truly works. What does it trust? Where does it make assumptions? How do its components communicate?

Armed with that mindset, and together with my colleague Sławomir Zakrzewski, we started exploring NetIQ Advanced Authentication version 6.4.2 – not by launching payloads, but by asking the right questions.

That approach led us to two CVEs:

- CVE-2024-10865: A Reflected Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)

- CVE-2024-10864: A Time-Based Blind PostgreSQL Injection

But more importantly, it led us to a deeper understanding of the system – and how subtle flaws can be chained into real, exploitable risks.

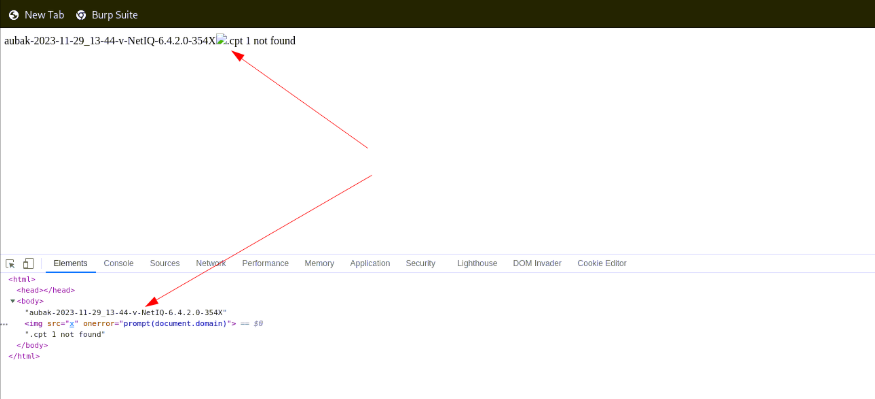

Chapter 1: File Not Found – XSS Found (CVE-2024-10865)

While exploring the application’s backup functionality, we noticed it required a specific file name and extension format. After digging into the documentation and reverse-engineering the validation logic, we eventually identified a valid filename pattern:

aubak-2020-10-10_13-44-v-NetIQ-6.4.2.0-354.cpt.Submitting this filename passed validation, but nothing interesting happened. The functionality itself was clean.

However, when we intentionally introduced an incorrect filename, the application responded with an error message that echoed the filename directly into the HTML response without proper sanitization. This led us to suspect a possible Reflected XSS vulnerability.

We tested that theory by submitting a file named:

aubak-2020-10-10_13-44-v-NetIQ-6.4.2.0-354<img src=x onerror=prompt(1)>.cpt…and indeed, the JavaScript payload executed in the browser.

What looked like a boring validation feature exposed a reflected XSS combined with the application’s verbose and unfiltered error messages.

Chapter 2: Exploiting PostgreSQL Injection via Default Credentials (CVE-2024-10864)

Our infrastructure scan revealed that port 5432 (PostgreSQL) was open. As a quick check, we tried logging in using the default credentials: postgres:postgres.

The connection was rejected – not due to invalid credentials, but because our IP wasn’t on the database’s whitelist.

That was interesting, but still a dead end… for now.

Later, while exploring the application’s admin panel, we discovered a feature for importing users from a database. It allowed us to specify the database address, credentials, and name. Naturally, we re-entered the PostgreSQL host and supplied the postgres:postgres combination.

This time, the application responded with:

"Invalid database name"This message confirmed something crucial:

The application successfully authenticated to the database, meaning those default credentials worked – we had just hit a bad database name.

So we tried the default PostgreSQL database: postgres.

Suddenly, a new message appeared:

"Users processed = 0, added = 0, updated = 0, deleted = 0"This revealed two things:

- The application could talk to the database.

- It attempted to execute some SQL logic – likely a

SELECTquery from a user table – but found no matching data.

At this point, things were still looking relatively tame. Even with valid credentials, the application could only import users, and we could not access their passwords or valuable content.

But we didn’t stop there.

We began to suspect that the application was dynamically constructing SQL queries using user-supplied parameters like the database and table names.

This was a perfect place to test for PostgreSQL injection if that were true.

So we injected the following into the database name field:

' or pg_sleep(10);--The server’s response was delayed by exactly 10 seconds.

Boom. Time-Based Blind PostgreSQL Injection Confirmed

We could begin exfiltrating arbitrary data from the backend database by carefully crafting payloads and measuring response times, even though we weren’t on the database’s whitelist.

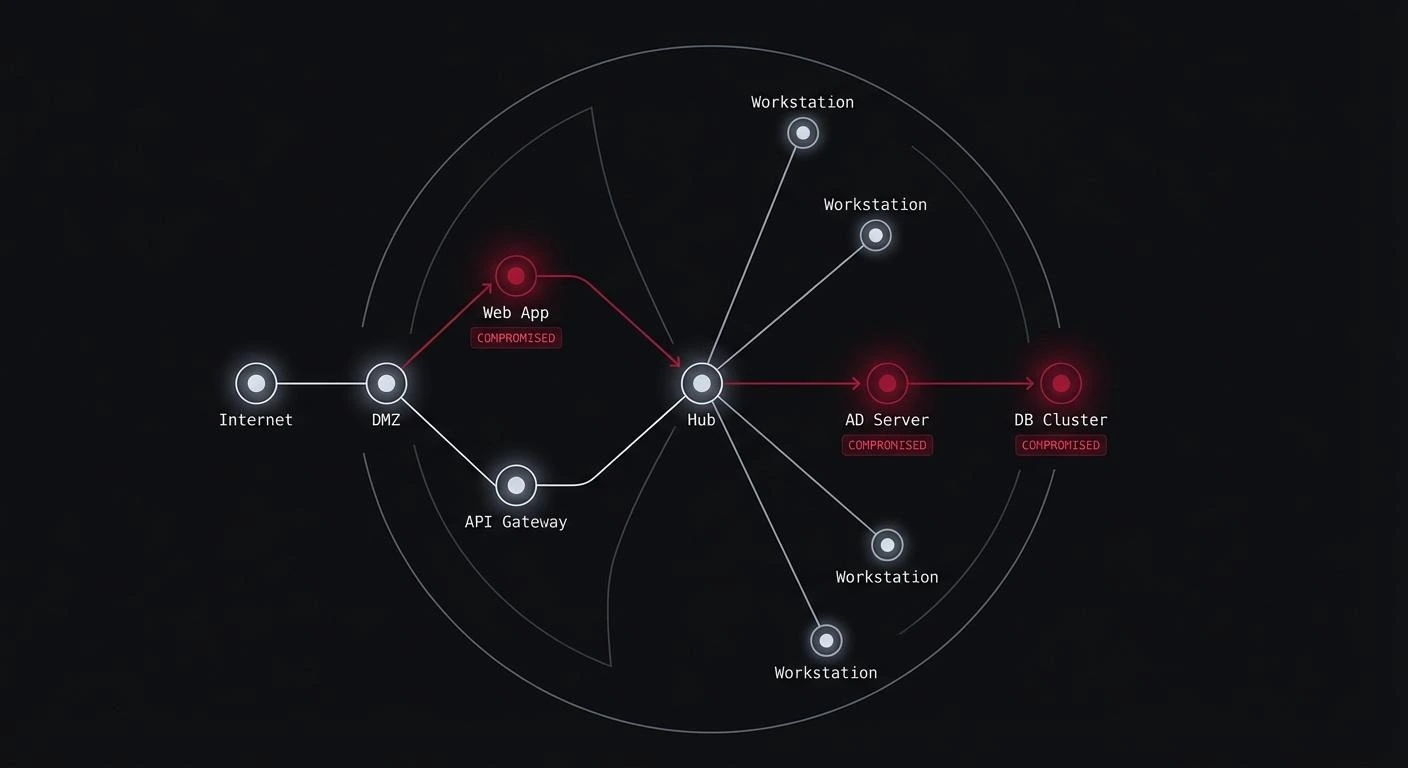

This worked because:

- The application itself was on the whitelist and acted as a proxy.

- The input fields were vulnerable to PostgreSQL injection.

- The default credentials were valid.

Although the presence of default credentials might have seemed like a low-impact misstep – and the SQL injection required those credentials to even be attempted – it initially looked like a vulnerability with near-zero impact.

But by understanding how the application was architected, we realized something far more powerful was possible.

The PostgreSQL injection vulnerability allowed us to abuse the import functionality to go far beyond importing existing users. We could extract any data from the database, bypassing IP restrictions and accessing sensitive content the application was never meant to expose.

Final Thoughts – Beyond Payloads

Security testing isn’t about throwing payloads at endpoints and hoping something breaks.

It’s about understanding the architecture, the trust boundaries, and the assumptions developers made along the way.

In this case, the vulnerabilities weren’t exposed by brute-force fuzzing or automated tools – they were revealed by understanding how the application handled backups, built database connections, and implicitly granted trust.

The difference between a feature and a vulnerability often lies in context.

And you only uncover that context when you take the time to learn how the system works.

Effective testing demands more than just creativity – it calls for curiosity and the discipline to slow down and think critically.

Credits

Huge thanks to CERT Polska for their support in coordinating the responsible disclosure process.

We also appreciate the professional and timely response from the team at NetIQ (now part of OpenText), who handled the reported vulnerabilities with care and transparency.

I would like to give special thanks to my colleague Sławomir Zakrzewski from AFINE, with whom I had the pleasure of conducting this research. Your insights and persistence made all the difference.

References

- CVE-2024-10864 – Time-Based Blind PostgreSQL Injection in NetIQ Advanced Authentication

- CVE-2024-10865 – Reflected Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) in NetIQ Advanced Authentication